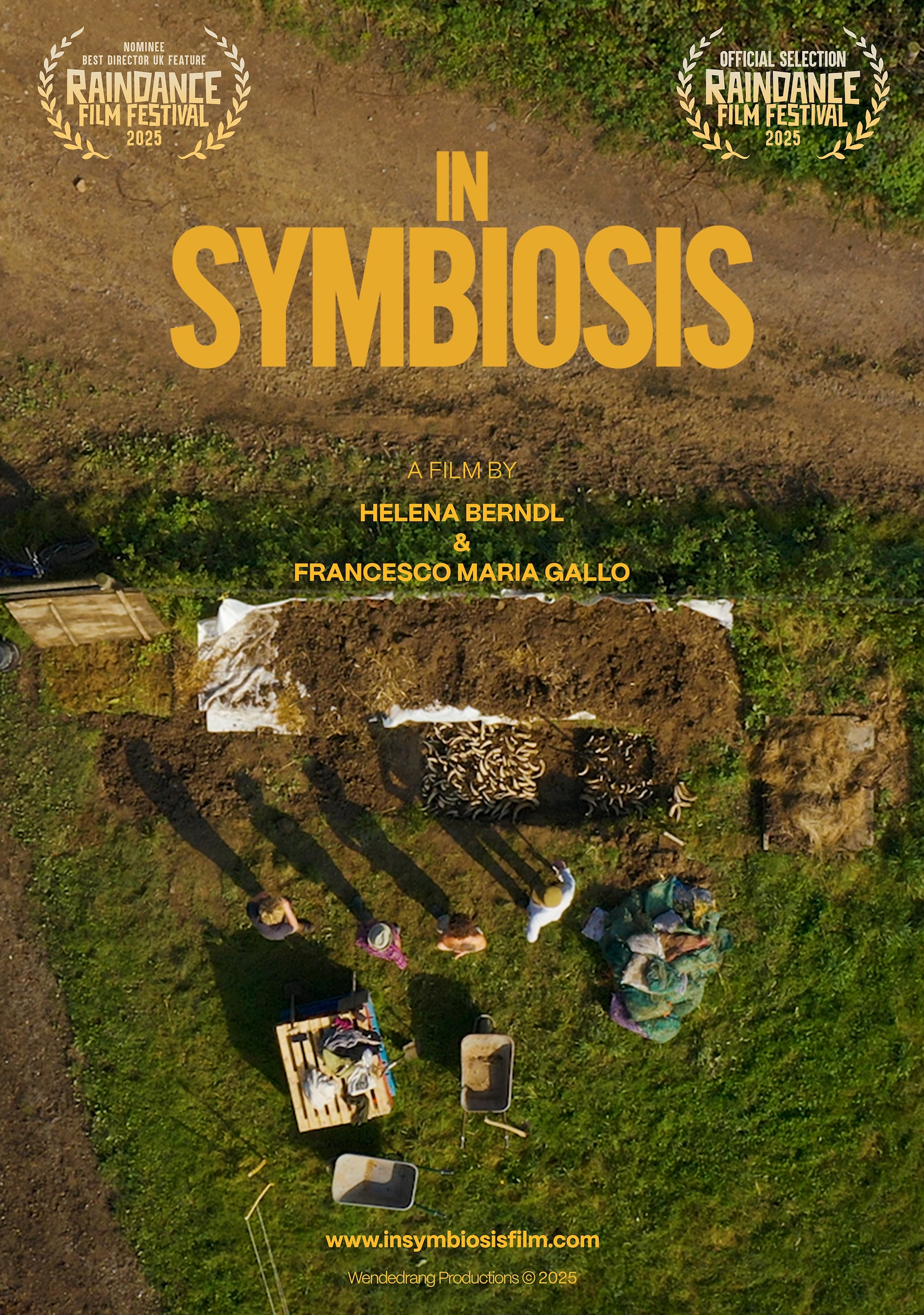

“In Symbiosis” unveils the driving forces behind a broken food system and puts forward a path to building true resilience

“In Symbiosis” unveils the driving forces behind a broken food system and puts forward a path to building true resilience

An inspiring and insightful new film, In Symbiosis, looks at what's gone wrong with food and farming (including the GMO and pesticides treadmill) and points to ways we can put them back on track towards greater sustainability and resilience. Directed by Helena Berndl and Francesco Maria Gallo, In Symbiosis features interviews with experts from across the world, including regenerative farmers, molecular geneticist Prof Michael Antoniou, GMWatch co-director Claire Robinson, and food sovereignty champion Dr Vandana Shiva.

The world premiere of In Symbiosis is in London on 24 and 25 June at the Raindance Festival.

Tue, Jun 24, 9:15 PM @ Vue Piccadilly - Screen 1

Wed, Jun 25, 3:15 PM @ Vue Piccadilly - Screen 3

See a trailer and book tickets here.

Don’t delay—tickets are selling fast. If you find that tickets are sold out, please ask the Raindance organisers to arrange a bigger screen or an extra showing.

Co-director Helena Berndl took time out of her busy schedule to give GMWatch the exclusive interview below.

Helena Berndl

GMW: You have a degree (MSci) in neuroscience from University College London. How did you come from this background to making the film – what was the journey?

HB: I have always had an interest in food, as I grew up with parents who had common sense about food and didn’t just do what everybody else did or what they were told to do. For instance, despite a strong push to buy margarine back in the 80s, because everybody said so, they tried it, but immediately said, “No, this is awful, we’ll stick with butter”. And whenever I wanted to pick up a fruity yoghurt in the supermarket, my dad would say, “Let’s not take this, it’s full of sugar and artificial things. You know what’s much nicer? We’ll buy the whole fruit, cut it up and add natural yoghurt to it.”

My mum, who grew up with an aunt who was the village herbalist in rural Poland, would always talk about the importance of a healthy gut microbiome, which medical doctors in Poland knew about and promoted back in the 1950s and 60s.

In addition, my dad’s relatives are – or were at some point during my childhood and teenage years – all farmers. So I have been exposed to farms from an early age and my mum grew as many of her own vegetables and berries as she could.

It was against this background that my interest in the food system evolved.

Then fast forward to my neuroscience studies in 2013. I was in year three when my sister Karin, who has been an inspiration and immense support throughout, asked me one day whether I knew anything about aspartame. My initial thought was that this is probably something people on the internet get a bit too flustered about, but I am an inquisitive person and always open to learning new things.

When I began to research this artificial sweetener, I remember being shocked about how much research there was, dating back to the 1960s/70s, and then the controversy surrounding it, and the story of how it was approved after years and years of back and forth of trying to establish whether it was safe for human consumption or not.

Around 92% of non-industry funded research suggested aspartame is not safe for human consumption, and yet it was approved by the US FDA (Food and Drug Administration) amid conflicts of interest and revolving door scandals between the agency, the manufacturing company G.D. Searle & Co., and the Reagan government. This was one of the key moments when I began to ask myself what is going on in our food system.

The other crucial aspect was the fact that when studying science, one comes to the realisation that the way science is typically communicated in the mainstream media to the public is often far from what is being said in the original research publication. In fact, some publications are not brought to the attention of the public at all, as they may not fit the current narrative at any given time.

I graduated with an MSci in neuroscience in 2015 and, although I started the degree with absolute conviction that I wanted to go into research, I began to understand that although I love attention to detail, overall, my interest lies more in putting individual pieces of the puzzle together and trying to communicate them truthfully.

It was around this time when a large number of documentaries focused on nutrition were emerging and causing a lot of confusion among people. My co-director, Francesco Gallo, and I were very interested and watched most of them. What we found fascinating was how each documentary managed to present research articles to back up their argument and hail the diet they suggested as “the diet” that will bring ultimate health and longevity to everyone on the planet. I found it confusing how, for instance, bread, which I grew up eating on a daily basis all these years (I should specify that it was sourdough bread from an Austrian village bakery), suddenly was being presented as one of the worst things we can eat, and how we all need to eat oily fish several times a week (typically advertised as salmon, which then drove the over-farming of salmon), without asking how it was grown or produced.

Not once did any of these documentaries at the time speak about how the way food is farmed and the way it is processed matters to give the final quality of the product. After watching what may have been the 20th documentary, I got fed up and thought something must be done. By this point Francesco, who is a wonderful cinematographer and cameraman, had made his first short film, Los Colores del Campo, a story about an ageing farmer and his son struggling to survive in a near-deserted village in Spain. It was a beautifully shot, heartbreaking story, which was the beginning of an eye-opening journey into the realms of modern-day food provisioning.

So, one day I called Francesco, and I was a bit nervous, because I thought he would probably laugh at me, but I just said, “Can we please make a documentary?” He immediately said, “Yes, let’s do it!”, and it went from there.

Francesco Gallo and colleague

GMW: Can you give a few examples of the people you interviewed for the film?

HB: Our very first interviewee was Daphne Lambert, an inspiring eco-nutritionist, who has a profound understanding of the importance of farming practices in human and societal health. She introduced us to Peter Brown, one of the most fascinating farmers and human beings we met on our journey.

Daphne also drew my attention to Prof Michael Antoniou at Kings College. I immediately began to explore Michael’s groundbreaking research in the field of GMOs and pesticides, and I understood straight away that this film could not be made without his extensive knowledge and contribution.

In the early years of our production, we also had the great honour of interviewing Peter Melchett, only six months before he sadly passed away. Further interviewees include the wonderful Nora McKeon, Vandana Shiva, Stefano Prato, Clovis Kabaseke, Claire Robinson, Julia Wright, Prof Carlo Leifert, Prof Richard Mulvaney and, crucially, farmers and growers from different regions, including Europe and Africa.

GMW: Thinking back to when you did your research/interviews for the film, this must have been an intense learning experience. What surprised you the most?

HB: We started off with a very strong core idea, which never really changed, namely the importance of the way we grow and process our food as the basis and the key to everything that follows. However, initially the thought was more confined to population health. This began to change over time as we pulled back curtains and saw things that we could not unsee, such as the issue of food security. We began to realise that the story of the food we eat today is much more complex than we had envisaged, and now the task became to convey this convoluted story clearly to the viewer. I remember talking to a well-known documentarian at the time who has made several films in this field and when I was describing to him what we are trying to do, he said: “Helena, you are trying to do the impossible.”

What surprised me the most was probably the fact that there is so much high-quality research out there, clearly demonstrating the detrimental impacts of various of the technologies employed in food production on human, societal and environmental health, and yet this is successfully drowned out in a sea of conflicting research publications, as well as news reports and film productions that create overall confusion and division.

GMW: What is the message that emerges from the film? What can ordinary people who care about our food and farming systems do?

HB: Not wanting to give away too much of the film at this point, I believe our documentary beautifully tells the story of why we are where we are with regard to our current food system, and that unless we consider the different elements, we will never understand the entire picture and proposed solutions may not bring the empowering change that is needed. At the same time, we strive not to preach, as we believe that the stories speak for themselves, and we never try to prescribe, but rather let the viewer form his or her own opinion along the way. Prescriptive ideas, I find, are often short-lived, as they do not form from within the person’s mind. The solutions are there, and they are pretty straightforward. They just are not supported in the same way as the dominant systems.

GMW: There’s a strong lobby in favour of the “GMOs and pesticides” model of farming. In your film, do you present the arguments in favour of that system, and if not, why not?

HB: Again, not wanting to give away too much about our film, I would say that we present arguments that invite the viewer to always evaluate and question events and technologies, to be open to different opinions rather than shutting them down, whilst taking into account who is providing the information, to have open and balanced discussions and, most importantly, to always look at the whole life cycle of any proposed solution.

Francesco Gallo filming

GMW: Now that you’ve finalised the film, what are your plans for the future? Do you hope to do more work in this field?

HB: Yes, absolutely. The current film is a beginning step, an overview of the situation, which hasn’t been done in this way before. We feel very strongly about social justice and equity, so it was our deepest wish to give a voice to those whose voices are often drowned out. It is what has kept us going throughout. Our film is a pure labour of love and, most importantly, we were able to remain independent and therefore true to our message. We would love to do more work in the field. There are so many stories to tell, and we hope we can be part of driving the change to a path of resilience for humans, societies, and the environment.

Photos courtesy of Helena Berndl