More Monsanto documents, more Tamar Haspel problems. Report by Paul D. Thacker

The University of Toronto, Faculty of Law is hosting a conference on food and law where I am appearing on a panel with other experts to discuss conflicts of interest and corporate influence. This presents a perfect opportunity to dive into a really understudied problem — in her recent book, NYU Emeritus Professor Marion Nestle found only 11 studies examining corporate influence on nutrition research — as well as address Tamar Haspel, a Washington Post food columnist who has a unique and conflicted approach to journalism.

First, a little history. Concerns that food companies might unduly influence science have dogged researchers since Philip Handler, the President of the National Academies of Science (NAS), proposed and helped pass the first conflicts of interest policy in 1971. (Curiously, Handler also consulted for several food and pharmaceutical companies, and served on the board of the food corporation Squibb Beech, leading to continuous criticism over his own industry ties.)

Scholars have traced corporate influence on science back to the tobacco industry, which in 1953 hired John W. Hill, the president of the PR firm Hill & Knowlton, to combat research linking smoking to cancer. To position tobacco as more science than the science itself, Hill orchestrated a campaign to create an alternative scientific reality that drowned out the voices of independent scientists and their impartial research. Sometimes referred to as the “denial playbook”, these tactics included funding university research that offered conflicting results, hiring academics as advisors or speakers, supporting vanity journals, and providing academic scholars with ghost written manuscripts to publish in peer-reviewed journals.

To further undermine independent scientists, tobacco also created think tanks and corporate front groups. These organizations echoed and amplified company studies and experts, countered articles in the media, and served as sources for reporters looking for “impartial” opinions for their news stories.

As noted by Professor Kelly D. Brownell, Director of the World Food Policy Center at Duke, the food industry later adopted strategies similar to tobacco’s, a move that exacerbated today’s obesity crisis. Indeed, Coca-Cola was caught a few years ago secretly funding an academic-led nonprofit called the Global Energy Balance Network, which worked to shift the debate away from soda as a cause of obesity to lack of exercise. As I reported for the BMJ, many of these academics involved in Global Energy also ran training programs for journalists that emphasized this same theme.

As with tobacco, a critical component to the food industry’s effort has been creating front groups — nonprofits that amplify corporate voices while appearing to be disinterested and independent. One of many players in food has been the industry-backed Center for Food Integrity. A 2007 email announcing the group’s formation notes that it was being formed in alliance with CMA Consulting, a PR and consulting business. Over the years, funders have included Monsanto, the American Farm Bureau, United Soybean Producers, United Egg Producers, American Meat Institute, and other trade organizations.

In a separate example, a study released this year examined over 17,000 pages of documents made public under freedom of information laws. That report found that the influential health charity International Life Sciences Institute (ILSI) is little more than an industry lobby group. In one damning incident, ILSI founder Alex Malaspina, a former Coca-Cola vice president, complained bitterly in a 2015 email about new US dietary guidelines for reducing sugar intake. He copied the email to ILSI’s then director, Suzanne Harris, and executives from firms such as Coca-Cola and Monsanto.

In a second incident, the Guardian reported that ILSI Europe’s vice-president Alan Boobis chaired a panel that found the pesticide glyphosate was probably not carcinogenic to humans. The panel’s report disclosed no conflict of interest statements, even though Monsanto had donated $500,000 to ILSI Europe and Croplife International had donated $528,500. Other media outlets have reported that ILSI runs a shadowy program to influence food policy in countries across the planet, including Brazil and China.

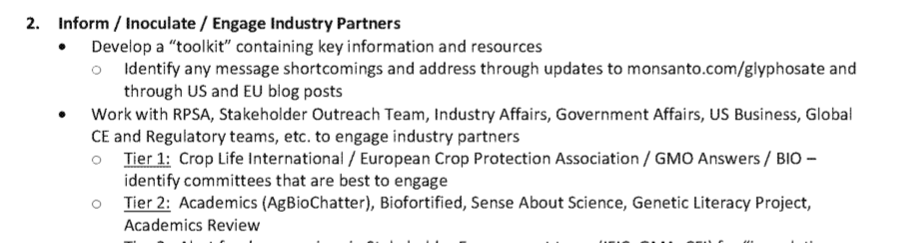

In the last few years, documents released during litigation against Monsanto regarding the carcinogenicity of their pesticide glyphosate have brought a plethora of information to light regarding tactics employed by the agrichemical giant and their allies. These documents show that Monsanto ran a concerted campaign to undermine the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), a World Health Organization cancer agency. Recognizing that IARC was about to classify glyphosate as a probable carcinogen in 2015, an internal Monsanto document notes the company launched a PR campaign that relied on allied industry partners to amplify their voices; those allied groups included Biofortified, Sense About Science, Genetic Literacy Project, and Academics Review.

Monsanto strategy documents to attack IARC

This program kicked off a multi-year campaign to attack IARC for finding glyphosate was a probable carcinogen. While attempting to portray the agency as a scaremonger that ignores actual human exposure to potential hazards, Monsanto lobbied US lawmakers to defund the agency. IARC’s director later told Politico that the agency had not witnessed such aggressive tactics since IARC classified second-hand smoking as a cause of cancer.

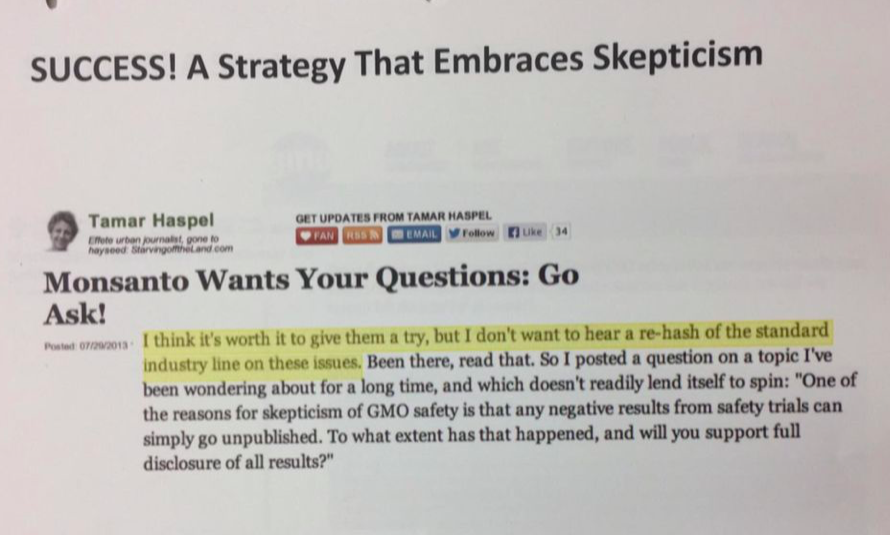

In part, Monsanto has been successful in their PR campaign by coopting some in the media. To that end, the company hired Ketchum PR to run a campaign called GMO Answers to reboot the discussion around GMOs and pesticides. When Ketchum launched GMO Answers in 2013, it was quickly embraced and promoted by Tamar Haspel, now a food columnist with the Washington Post. As I wrote for Huffington Post, Haspel has long had cozy ties to the agrichemical industry, often attending talks they sponsor through allied groups and academics.

Ketchum internal document regarding GMO Answers

In one example, Haspel attended a junket organized by Professor Kevin Folta and sponsored by Academics Review and the Genetic Literacy Project. Journalists were offered a $2500 speaking fee. Kevin Folta and the leaders at Academics Review and the Genetic Literacy Project were later exposed for financial ties to Monsanto.

The Huffington Post article presented Haspel with a moment to reconsider her behavior, and think more critically about corporate influence on food policy and reporters. Perhaps show a little more curiosity in the people she quoted and the groups inviting her for speaking gigs? However, instead of seizing that opportunity and apologizing, she doubled down, promoting herself as a paragon of journalists ethics.

Responding to the Huffington Post, Haspel wrote: "Folta’s ties to Monsanto were revealed after the event I spoke at (as were those of Academics Review and Bruce Chassy); it’s telling that this makes no difference to the author or HuffPost; I’m still accused of participating with scientists and groups with ties to Monsanto. I worked with none of the people or groups after the disclosure (the events I participated in were in 2014 and May of 2015)."

Unfortunately, Haspel’s claim of ignorance is hard to swallow. To begin with, anyone with access to Google could have looked up Genetic Literacy Project’s executive director, Jon Entine. In 2012, Mother Jones reported on Entine’s close ties to Syngenta and the American Council on Science and Health, an organization long criticized as an industry front group. And even if she missed that article, Haspel could have learned about Entine’s work helping Syngenta in their decade long campaign to attack Berkeley scientist Tyrone Hayes.

The article that detailed that campaign appeared in 2014, in a fairly well-known magazine called The New Yorker.

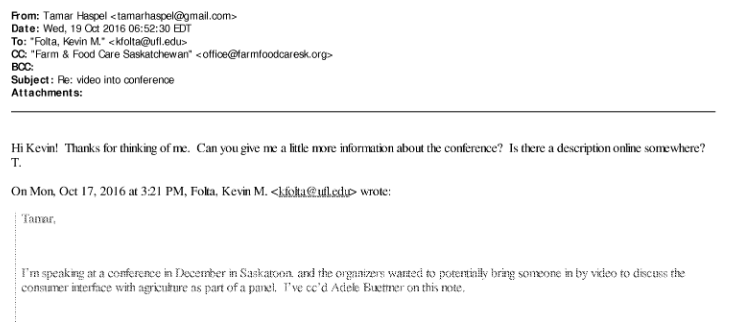

Moreover, Haspel’s claim that she never again worked with these people after their ties to Monsanto were exposed is incorrect. Again, we know this from emails. A year after the New York Times exposed Kevin Folta for his hidden financial ties to Monsanto in 2015, he emailed Haspel in 2016 to invite her to appear as a speaker at a conference he was attending. Haspel responded, “Thanks for thinking of me. Can you give me a little more information about the conference?”

Emails between professor Kevin Folta and Tamar Haspel in 2016

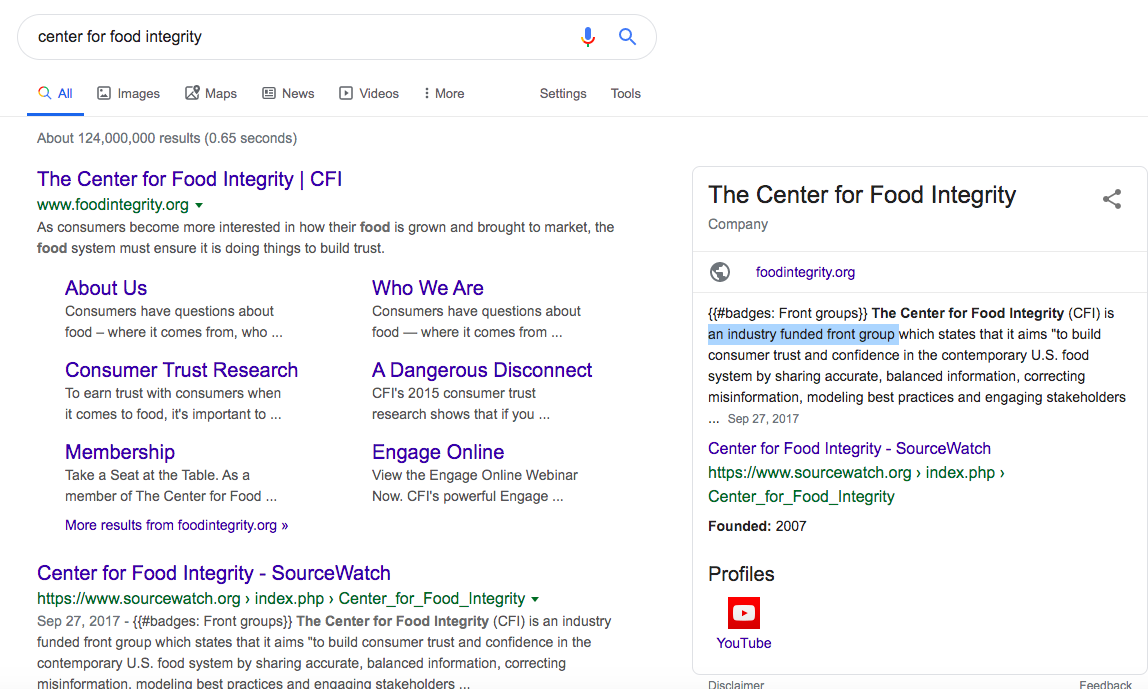

Her much hyped conflicts of interest and disclosure policy regarding her speaking gigs leaves much to be desired. In one example, she discloses giving a talk for the Center for Food Integrity, without mentioning its ties to industry. Again, this is a simple catch with Google where much of this information can be found and confirmed at the group’s Sourcewatch Page.

Google results for Center for Food Integrity

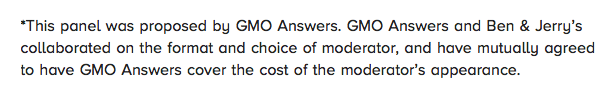

In another example, she lists this speaking engagement: “South By Southwest, Austin TX (debate between GMO Answers and Ben & Jerry’s)”. In reality, the event was run by Monsanto’s GMO Answers, as they proposed the panel and picked up the costs.

More examples like this exist on Haspel’s website, but why beat a dead conflict of interest policy?

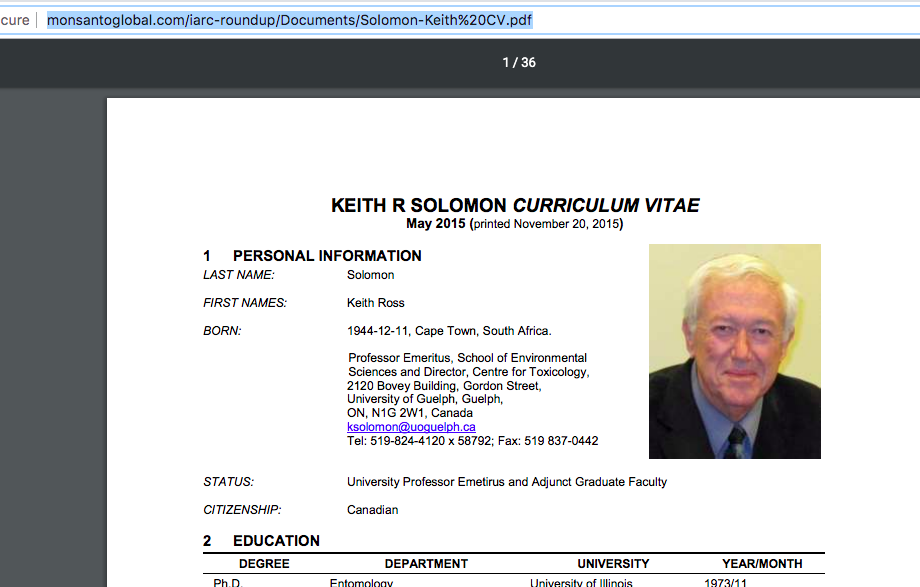

The latest documents, released from litigation, show that an error-riddled piece on glyphosate that Haspel wrote for the Washington Post in October 2015 delighted industry lobbyists. And why not? In her column, Haspel quoted from Keith Solomon, an environmental toxicologist who was consulting at the time for Monsanto. We know he was doing so, because his May 2015 CV was posted on Monsanto’s website.

Keith Solomon’s CV found on the first page of Google results

Again, do not fear the Google.

What must have most excited Monsanto was that Haspel botched her discussion of the chemistry of glyphosate. When studying potential harm, researchers measure both glyphosate and its main metabolite — AMPA — as the chemicals have similar toxic profiles. In fact, some medical experts have published studies that found AMPA can kill cancer cells lines in petri dishes, because it promotes apotosis, or cell death.

But Haspel screwed up this piece of the metabolic puzzle, seeming to imply that because AMPA can kill cancer cells in a petri dish, glyphosate might inhibit rather than cause cancer in people. Haspel’s column was then promoted on the websites of Monsanto allies — the Genetic Literacy Project and the American Council on Science and Health.

Genetic Literacy Project promoting Tamar Haspel column on glyphosate

American Council on Science and Health promoting Tamar Haspel column on glyphosate

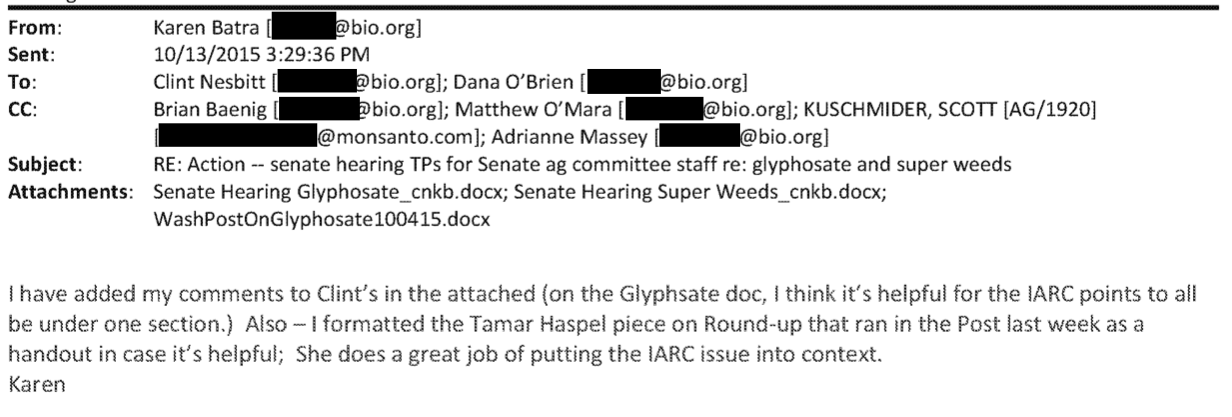

A week after Haspel’s piece ran, the Senate Agriculture Committee held a hearing to examine GMO technology and the potential dangers of glyphosate. The set-up of the hearing annoyed some consumer watchdogs, which protested that the hearing did not include representatives of consumer groups that supported mandatory labeling of GMO food. Industry, on the other hand, was not worried; in fact, it was more concerned with how to use Haspel’s recent article to its benefit.

While putting together talking points to influence Senate staffers, a lobbyist emailed his colleagues, “Also — I formatted the Tamar Haspel piece on Round-up that ran in the Post last week as a handout in case it’s helpful; She does a great job of putting the IARC issue into context.”

Email between industry lobbyists promoting Tamar Haspel column to Senate Committee staff

Earlier this year, Berkeley journalism professor Elena Conis wrote a piece for the Washington Post that clearly explained the science of glyphosate. When it first came on the market in 1985, EPA scientists classified it as a carcinogen but reversed that decision because of industry pressure. Monsanto then commissioned its own research from favored scientists and asked federal regulators to base decisions on those studies. To this day, we are dealing with the fallout of Monsanto’s paid-for research that argues glyphosate is safe.

As criticism has grown over the years regarding Haspel’s pro industry reporting, she attempted to pose as a referee in the pages of the Washington Post last year, calling on all sides to stop with the name calling.

Before this particular Haspel column, dozens of scientists had expressed dismay about industry’s attack on IARC in Environmental Health Perspectives, with later outcries in American Journal of Industrial Medicine, American Journal of Public Health, and the Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health. Haspel took a different tack in her article: ignoring scientists’ concerns, she held up media personality Mark Lynas as a voice of reason on controversies in agriculture.

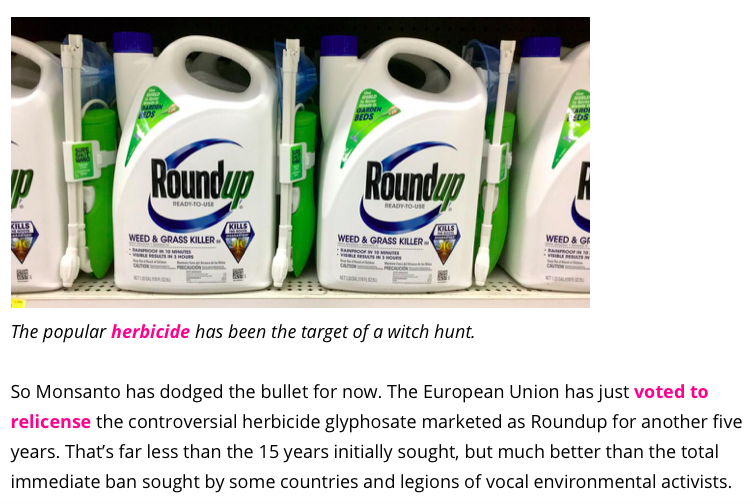

However, a year prior, Lynas wrote a screed against IARC, hyperventilating that its classification of glyphosate as a probable carcinogen was hysteria and an example that “Europe still burns witches if they are named Monsanto.” Despite this rant, Haspel morphs Lynas from arsonist to fire chief.

Mark Lynas column castigating IARC, the World Health Organization’s cancer agency

In many respects, corporate influence is pervasive in food because researchers in the field have little to no understanding of the research around conflicts of interest — unlike researchers in medicine. The first conflict of interest policy at a journal was instituted in 1984 at the New England Journal of Medicine and JAMA did the same the next year. The journal Science didn’t bother to do the same until 1992, with Nature waiting until 2001.

With the passage of the Physician Payments Sunshine Act, anyone can look up a doctor and see who they are taking money from. Yet, the only tools available for monitoring researchers in food and nutrition are the freedom of information laws and documents made public during litigation. As expected, Monsanto has been leading a campaign against freedom of information requests.

We can expect controversies and continued poor reporting in the food and agriculture arena until conflict of interest standards are tightened. Ethical considerations long recognized in medicine should be implemented, and readers should expect more documents to be released in litigation to shed light on industry PR campaigns.

Paul D. Thacker is a journalist and writer based in Madrid, with bylines at WashPost, BMJ, Yahoo and more. He is a former congressional staffer and consultant to a brain disorder nonprofit.

This article was first published on Medium.com. It is republished on GMWatch by kind permission of the author.