Orwellian moves to redefine our concept of nature aim to gain public and regulatory acceptance for risky technologies. Report: Claire Robinson

Those who are watching the UK government's moves to "deregulate" (remove regulatory controls from) GMOs will have noticed the attempts to normalise genetic engineering in the mind of the public, policymakers and regulators by using the terms "nature", "natural" and "naturally" to describe the changes brought about by GM techniques like gene editing, which are claimed merely to "mimic the natural breeding process". The motivation appears to be to create a sense of safety and familiarity around genetic engineering that will defuse opposition to deregulation.

We view these developments as unscientific as well as dangerous, since research shows that the changes brought about by gene editing are different from what could happen naturally and pose special risks.

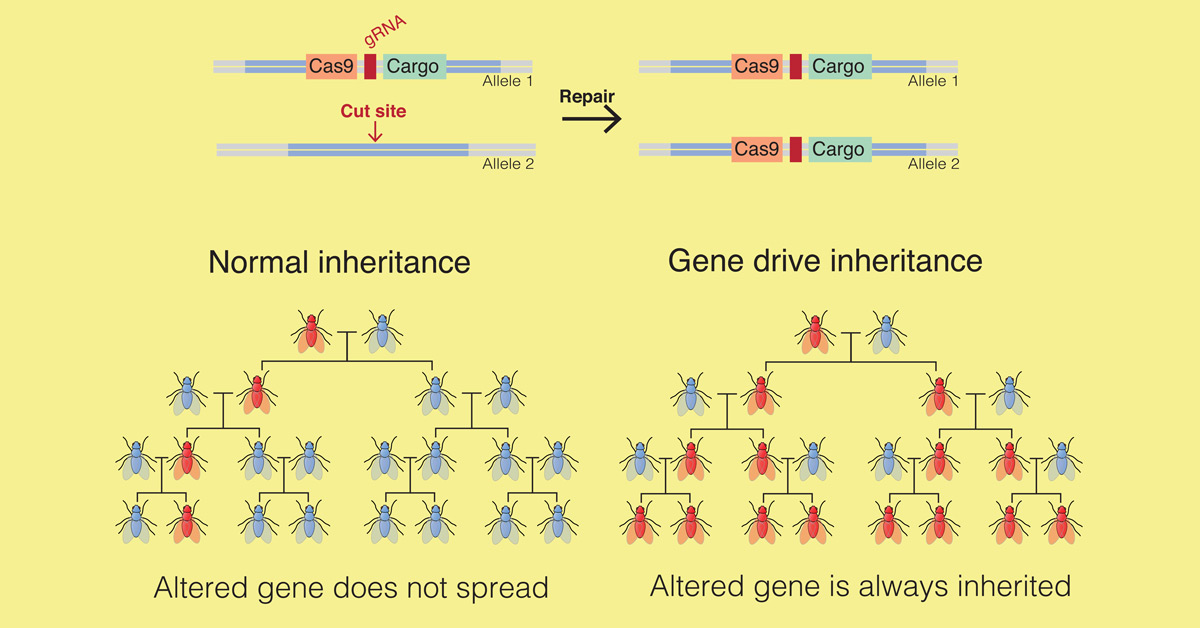

Now similar Orwellian moves are happening in the area of gene drives. A gene drive is a genetic engineering technology that forces a particular genetic modification through a population by changing the natural rules of inheritance, usually to ensure that it is increasingly – or always – inherited. Gene drive organisms are built to intentionally spread their engineered traits through an entire population, turning on its head the usual imperative to try to contain and prevent engineered genes from contaminating and disrupting ecosystems. They can be designed to re-model or delete entire species.

Gene drive technology is deeply unpopular and rightly feared by the public and regulators. It is against this background that in recent years, some researchers have begun to describe so-called "selfish genetic elements" found in nature* as "natural gene drives" and to present gene drive as a "ubiquitous natural phenomenon".

In line with this trend, in an opinion piece published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), a group of gene drive developers, including Luke Alphey, Andrea Crisanti, and Omar Akbari, attempt to redefine gene drives as natural.

In their article, "Standardizing the definition of gene drive", Alphey and colleagues argue that "gene drives are a natural phenomenon. They have arisen through entirely natural processes of mutation and selection; indeed many types exist... and gene drives and relics of old gene drives are widespread in nature." They claim that "modern molecular biology" now allows genetic engineers to "mimic various types of natural gene drives in the laboratory".

As supplementary data to their paper, they publish a terminology glossary "to prevent confusion in the field", which clearly categorises certain naturally occurring genetic phenomena as gene drives.

Now two scientists, Dr Mark A. Wells and Dr Ricarda Steinbrecher, have published a commentary in PNAS challenging Alphey and colleagues' stance. Drs Wells and Steinbrecher write, "The definition of the term 'gene drive' Alphey et al. propose would include naturally occurring selfish genetic elements (SGEs) and natural processes causing biased inheritance. We disagree with this aspect of the proposal, which does not reflect the original use of the term, which related to engineered systems. The altered definition has the effect of emphasizing the similarity of engineered gene drives to natural SGEs by allowing both to be described as 'gene drives'."

This is misleading, they add, as "The use of this [engineered gene drive] technology brings serious risks – we therefore are concerned that the proposed terminology presents engineered gene drive systems as repurposed natural entities. This unfortunately brings connotations of safety and familiarity that will discourage the necessary scrutiny. We thus regard the proposed definition as problematic in the context of political and regulatory discussions concerning this technology.

"For example, we find it worrying that an International Union for Conservation of Nature report, which will be influential in the regulatory debate in the conservation community, introduced 'gene drive' as 'a ubiquitous natural phenomenon'."

They point out, "There are significant differences between the engineered and natural systems which play out at the level of risks. Engineered gene drive systems would evidently be used to serve human intentions. While these intentions themselves deserve scrutiny, they will also fundamentally affect the composition, properties, and genomic context of the resulting engineered elements."

They conclude: "In our view a narrower definition, with intentionality and use of genetic engineering as defining features, is more appropriate, especially in the context of risk assessment."

The importance of semantics

The moves to redefine gene drives as natural are reflected in the semantic sleight-of-hand practised by the lobby that wishes to deregulate gene editing. A statement signed by over 100 international scientists and policy experts objects to the increasing use of the term "precision breeding" to describe the imprecise technique of gene editing. The term seems calculated to give a sense of naturalness and control. The GMO and pesticide promoter Kevin Folta dismissed the scientists' statement as nothing but "semantics".

But words matter, as George Orwell taught us. And given that regulation and law depend entirely on "semantics" – the branch of linguistics and logic concerned with meaning – we interpret Folta's tweet as confirming the crucial importance of both the statement and the new paper by Drs Wells and Steinbrecher. The concept of nature itself is being twisted to force an acceptance of technologies that could have serious or even catastrophic consequences.

---

The new commentary:

Wells, Mark A, and Steinbrecher, Ricarda A. “Natural selfish genetic elements should not be defined as gene drives.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America vol. 119,34 (2022): e2201142119. doi:10.1073/pnas.2201142119 https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2201142119 (open access)

* Such as transposons, nucleic acid sequences in DNA that can change their position within a genome, sometimes creating or reversing mutations and altering the cell's genetic identity and genome size.

Image by Mariuswalter via Wiki Commons. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International licence.