Excerpt from Don't Worry, It's Safe to Eat, by Andy Rowell

Below is chapter 6 of Andy Rowell's book, Don't Worry, It's Safe to Eat, first published by Earthscan in 2003 and republished by Routledge in 2015. The chapter continues the story of what happened to the eminent scientist Dr Arpad Pusztai after he revealed on British television that GM potatoes caused serious harm to the health of experimental rats. The preceding chapter is here. Both chapters of the book are reproduced exclusively on GMWatch with kind permission of the author.

---

CHAPTER 6: The ‘Star Chamber’

‘The Royal Society decided that, in view of the high profile given by some groups to Dr Pusztai’s work, it would be in the public interest for the data available to be subject to independent assessment by other experts’

Dr P Collins, The Royal Society

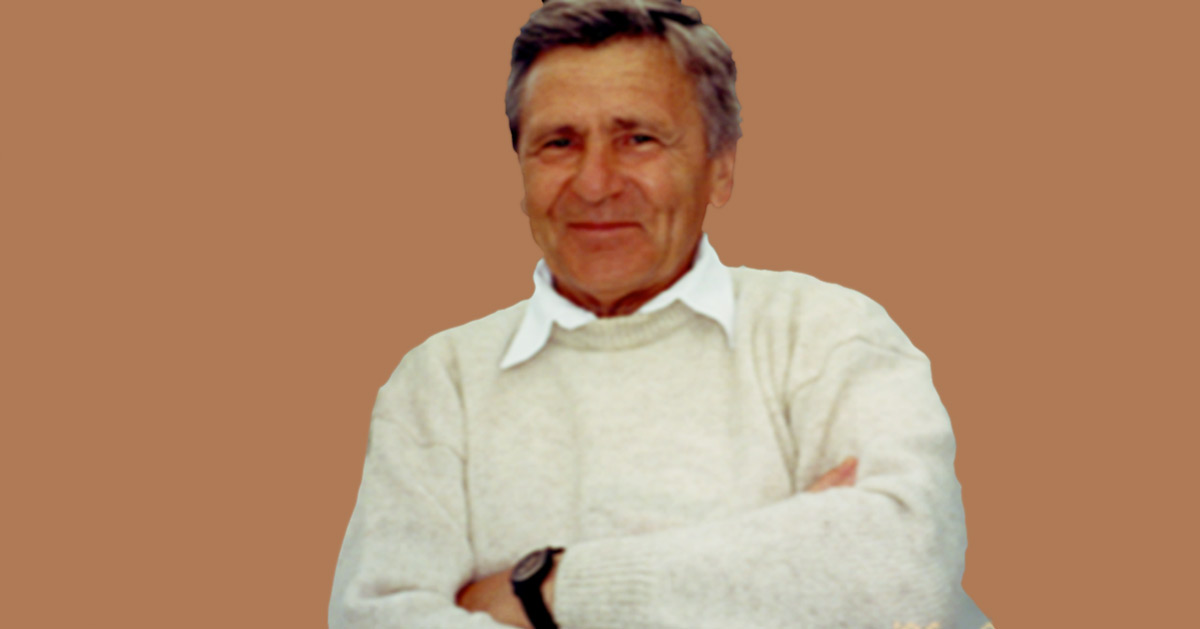

‘Their remit was to screw me and they screwed me’

Arpad Pusztai

The Royal Society

A week after the international scientists backed Pusztai (see Chapter 5), a secret committee met to counter the growing alarm over GM. Contrary to reassurances by the government that GM food was safe, the minutes show the cross departmental committee formed to deal with the crisis, called MISC6, knew the reassurances were premature. It ‘requested’ a paper by the Chief Medical Officer (CMO) and the Chief Scientific Advisor (CSA) on the ‘human health implications of GM foods’.

Once again a government – this time Labour – was reassuring the public that food was safe, when quite clearly they did not know. What would happen, the minutes asked, if the CMO/CSA’s paper ‘shows up any doubts? We will be pressurised to ban them immediately. What if it says that we need evidence of long-term effects? This will look like we are not sure about their safety’.[1]

That very same day – 19 February – The Royal Society publicly waded into the Pusztai controversy. ‘The Royal Society is establishing an independent expert group to examine the issues related to possible toxicity and allergenicity in genetically modified plants for food use’, read the press release. ‘Eminent scientists will be asked to review published and unpublished data. Their views, reached individually and independently, will be considered by a Royal Society expert panel, which will subsequently produce a report.’[2]

The review, which was instigated by the President and Vice-President of the Society, was set up ‘in response to increased public concerns arising from conflicting media reports about the potential benefits and dangers of GM foods’. Four days later, the then President of the Society, Sir Aaron Klug, told the Parliamentary and Scientific Committee that ‘the use of GMO’s has the potential to offer real benefits in agricultural practice, food quality and health, although there are many aspects of the technology which require further research and monitoring’. Then in a veiled warning to Pusztai, Klug continued: ‘I would stress that premature, partial or selective release, or misinterpretation of unsubstantiated research only serves to mislead the general public in a complex area.’[3]

Klug was backed by 19 Royal Society Fellows in a letter published in the national press. Included on the list was Sir Richard Southwood, whose Committee on BSE was widely criticized, and Professor Roy Anderson who would be widely criticized for his un-peer-reviewed models on foot and mouth, two years later.

Other signatories included Professor William Hill and Professor Brian Heap, who was to be on The Royal Society’s Pusztai working group and Peter Lachmann, who was later accused by the Editor of The Lancet of threatening behaviour over his decision to publish Pusztai and Ewen’s paper. The letter read: ‘Those who start telling the media about alleged scientific results that have not first been thoroughly scrutinised and exposed to the scientific community serve only to mislead, with potentially very damaging consequences.’[4]

The first salvo had been fired from the prestigious offices of The Royal Society in Carlton House Terrace. Formed in 1660, The Royal Society is the world’s oldest scientific organization, and past patrons include Samuel Pepys, Christopher Wren and Isaac Newton. Its current Patron is the Queen. It is the pillar of the scientific establishment, the scientific equivalent of the exclusive old boy’s club.

Writing ‘FRS’ (Fellow of The Royal Society) after your name has long been the aim of many scientists, but it is joked that it is easier to win the Nobel Prize than to be elected to this august body.[5] Nearly half of its members are from just three Universities – Oxford, Cambridge and London, known as the scientific ‘Golden Triangle’.[6] ‘It remains a selfperpetuating elite,’ says Moira Brown, a professor of Neurovirology at Glasgow University. ‘Old, white and male.’[7]

In its investigation into ‘Learned Societies’, the Commons Science and Technology Committee found that 60 per cent of current Fellows are over 65 and only 3.7 per cent of fellows are female. The committee also criticized the Society’s ‘head in the sand attitude’ attitude over race issues.[8]

Ever since its foundation The Royal Society has seen itself as the ultimate arbiter of scientific truth. But the last 40 years has seen The Royal Society change its role. Until 1960, The Royal Society’s publications had carried a disclaimer in every issue stating ‘it is an established rule of The Royal Society … never to give their opinion, as a Body, upon any subject’.[9] Since then The Royal Society have become the scientists ‘trusted’ by government – the gatekeepers of reliable knowledge.[10] It is now the official voice of UK science. But its official primary objective is to promote ‘excellence in science’, and it states that it has three roles, as the UK academy of science, as a learned Society and as a funding agency.

The justification for its review of GM foods, argues The Royal Society, was Pusztai’s comments on the World in Action programme. ‘The work on which these claims were based had still not been accepted for publication in a peer-review journal in February 1999, nor had it been presented to other experts at a scientific conference.’[11]

However, here The Royal Society is both right and wrong. They are correct in saying that Pusztai and Ewen’s paper had not yet been published in The Lancet, although it had been submitted the previous December. But they are wrong, in that in November 1998 Pusztai and Ewen had been invited, along with Philip James and Andy Chesson, from the Rowett to a scientific meeting in Lund in Sweden, where 40 senior lectin specialists and European scientists attended a meeting of the COST 98 Action Programme of the European Union.[12]

Professor Bøg-Hansen, a senior professor from the University of Copenhagen, and one of the organizers, recalls how ‘neither Professor James nor Dr Chesson were willing to participate or even reply to the invitation which is all the more regrettable because during the meeting Dr Ewen presented his findings’. Bøg-Hansen notes that ‘conclusive evidence that raw GM potatoes has a profound physiological effect’ was ‘reported by Dr Ewen’. Pusztai too gave a paper, but because he was still officially gagged, this was not included in the conference proceedings, as Ewen’s was.[13]

So, by February 1999, an abstract of the Pusztai and Ewen research had been published and discussed at a scientific conference, totally undermining the very reasons given by The Royal Society as a justification of their review. ‘Did they have the right to peer review an internal report?’ asks Dr Pusztai. ‘They have never done it before and I had never submitted anything to them. They took on a role in which they were self-appointed, they were the prosecutors, the judges and they tried to be the executioners as well. I see no reason why I should have cooperated with them in my own hanging.’

The Royal Society had already entered the GM debate a month after the screening of World in Action the previous August, issuing a report entitled ‘Genetically Modified Plants for Food Use’. This meant the Society could ‘update’ their report. On 5 March 1999, the Executive Secretary of The Royal Society, Stephen Cox, wrote to Pusztai and Stanley Ewen. ‘The Royal Society is carrying out a review of safety issues related to GM food’, the letter read, ‘in view of recent concerns regarding genetically modified food, we will be re-visiting the section of our [1988] statement that dealt with toxicity and allergenicity of GM food.’

But The Royal Society just planned to examine Pusztai’s work. ‘If you look at their original letter’, comments Pusztai, ‘it says that were going to update the original Royal Society report, but what it came down to was condemnation of Pusztai and nothing else.’ This is denied, though by the Society, who maintain that the review was not about ‘individuals,’ but was an examination of the science and the serious issues raised in the media coverage of GM, although no other scientist was mentioned.

On 15 March Stephen Cox wrote again to Pusztai and Ewen,[14] and four days later Pusztai responded. ‘We have now managed to recover all our primary data from Rowett notebooks and worksheets’, he wrote. This data had been subjected to an independent statistical analysis and now formed part of a final report which in turn formed part of Pusztai’s submission to the House of Commons Science and Technology Committee, although this remained confidential.[15]

The two parties are at odds over why The Royal Society never received this crucial evidence. Pusztai maintains that it was the Science and Technology Committee who insisted that this report stay confidential. ‘I told them there was an updated report sitting with the Science and Technology Committee. It is really only a couple of weeks, and then this updated report could be made available to them. They simply ignored it. They obviously had an agenda to make a judgement and this might have been embarrassing because it was an independent statistical analysis’. However, The Royal Society say that the Clerk of the Committee ‘assured’ them that Pusztai was free to give this data to ‘anyone else’, so long as he had asked the committee first.

In his letter of 19 March Pusztai wrote ‘I am anxious to cooperate with you on this even though the omens are not the best… I think it far more important to be right than to rush to print in advance of being able to make a balanced and true statement on this weighty matter.’[16] Pusztai then explained that he was going on holiday from 24 March until 14 April.

The day before Pusztai left for his holiday, Stanley Ewen responded to The Royal Society too. ‘My respectful suggestion would be to postpone your intended meeting to permit the present tense atmosphere surrounding GM food to subside analogous to the way that the Rowett Research Institute handled the problem initially on 12.08.98,’ wrote the distinguished pathologist. ‘Public anxiety is heightened at present and further media attention might be averted. For my part, I feel that I don’t wish to be manipulated, in this inappropriate manner, until my findings are fully published in peer-reviewed journals.’

‘On the other hand,’ continued Ewen, ‘I would be happy to address the main working group so that the entire effect on the gastrointestinal tract can be seen and explained. I would be able to defend myself with back ups of my photomicrographs in any forum but the photographic evidence, in isolation, would be inadmissible without expert interpretation. I presume that your proposed working group would be truly and transparently independent of biotechnology companies and that I could be represented, for example, by the President of the Royal College of Pathologists, on your working group’.

Ewen offered to send The Royal Society the scientific abstract that he had prepared the year before for the Lund meeting, the evidence that had already been presented to his scientific peers. He concluded ‘I do hope that your working group will represent the “defence”, as well as the prosecution’.[17] Ewen was not asked to attend any meeting or send the scientific abstract.

In reply to Pusztai’s letter, Stephen Cox, gave a written assurance that: ‘It is important that the Society considers all available, relevant data so that an accurate and comprehensive statement can be produced.’ The letter was dated 23 March, so The Royal Society knew there was a fair chance that it would not arrive in Aberdeen before Pusztai left to go on holiday the following day.[18]

In fact, The Royal Society had begun sending out information to reviewers on 19 March, and just over a week after they wrote to Pusztai, the Society starting receiving its anonymous reviews back. The first review was written by a ‘physiologist with an interest in nutrition’. The handwritten review commented that: ‘I have already commented on the investigations at the Rowett Research Institute and have nothing further to add… This was pioneering work, but more research needs to be done.’[19] This implies that the reviewer had already made comments about Pusztai’s work and therefore should not have been a reviewer.

The second reviewer lamented that there was ‘no convincing evidence of effects on growth, organ development or immune function of transgenic potatoes expressing GNA lectin’.[20] The third ‘found the data impossible to referee in the usual sense since proper descriptions of methodology are missing’.[21] The fourth did state that ‘the independent statistical report is of a high and reliable quality’.[22] The fifth suggested more work was needed.[23] The final reviewer felt that, at worst, the preliminary findings were ‘alarmist’, but also recommended further research.[24]

On receiving these reviews when he returned from holiday, Pusztai responded that ‘I am afraid that The Royal Society has obviously not accepted my offer of cooperation but proceeded regardless with the review without taking up my offer of a personal input into your review process. As it is, therefore, The Royal Society’s decision was to sit in judgement of me rather than trying to establish the truth’.[25]

Then, on 13 May, the Society faxed Pusztai a ‘revised’ review from the sixth reviewer, which arrived 45 minutes before the deadline for Pusztai to comment. The Royal Society argues that it on the reviewer’s ‘own initiative’ that the review was rewritten. Pusztai notes that some wording was changed, all for the worse. The first draft had said there were several factors that would ‘urge caution in the interpretation of the data’.[26] The revised draft noted these factors ‘urge that the data are unsafe’.[27]

The day before, 12 May, Pusztai had written to The Royal Society saying it was ‘totally inappropriate’ to peer-review internal reports from the Rowett. He asked that ‘in view of the incomplete nature of the information provided to your reviewers their comment so far obtained will be held in suspense and not be published.’[28]

But it was to no avail. On 18 May The Royal Society issued its damning verdict against Pusztai, at a press conference. The report said that Pusztai’s work was ‘flawed in many aspects of design, execution and analysis and that no conclusions should be drawn from it’.[29] In its first paragraph, The Royal Society said ‘we have reviewed all available data related to work at the Rowett Research Institute’. At best this was misleading, because The Royal Society knew that other data was available.

Their second paragraph was slightly clearer – on the ‘basis of the information available to us’, [emphasis added]. When asked about this, The Royal Society replies that: ‘we reviewed all the data available to us; obviously we could not review data that was said to be forthcoming… However, the working group felt that they had received sufficient information to make an accurate assessment of the experiments carried out on GM potatoes’.[30]

The one word that mattered was ‘flawed’. ‘GM research “flawed in design and analysis”’, said The Guardian. ‘Experts Say Key Research is Flawed’, echoed The Daily Mail.[31]

The fact that his work was condemned as ‘flawed’, contrasts, Pusztai believes, with the fact that he had had over 30 articles published in peer-reviewed journals using the same methodology and groups of international experts had backed his work. Moreover Pusztai’s team had won the contract ahead of 28 other contenders, and the Scottish Office had checked his methodology. In August that year Pusztai published a paper on genetically modified peas in the Journal of Nutrition in the USA.[32]

The referees for that paper were fully supportive, argues Pusztai. ‘We have been using the same design for a long time.’ But that paper concluded that transgenic peas could be used in rat diets ‘without major harmful effects on their growth, metabolism and health’.[33] It was the same methodology, but different outcome.

‘I think The Royal Society were rather savage and extreme because they were offended by Arpad’s crude experiments as I was,’ says Professor James, Pusztai’s ex-boss, ‘but that is different from saying that he did not have a story there’.

One food safety veteran, Professor Lacey, thought the Society’s attack on Pusztai was ‘absolutely grotesque. I don’t know if his particular research is indicative of human hazard or not, all I know is that you cannot do experiments to find out ultimately. That is the whole key. If you cannot test a hypothesis, then you have to assume a hazard unless, over centuries of experience, you do establish safety.’

The House of Commons Select Committee

The same day, 18 May, the House of Commons Science and Technology Select Committee attacked Pusztai too. According to the committee, ‘Dr Pusztai’s interpretation of his research data was disputed, not only by the Rowett Institute, but also by an independent statistical analysis, commissioned by Dr Pusztai himself, which found “no consistent pattern of changes in organ weights” and which questioned the validity of the design of the experiment. Dr Pusztai told us that in his 110 day feeding trials, “no differences between parent and GM potatoes could be found”. This directly contradicts his statement on World in Action. Dr Pusztai’s appearance before us attracted far more press interest than did some of our more credible witnesses’.[34]

This is a highly damaging attack on Pusztai and one he feels is very misleading. On two crucial occasions when Pusztai tried to explain himself, the Chair of the committee cut him off, on one occasion saying that ‘we do want to try to keep the science to a minimum’.[35] The Chair of the committee suggested a private meeting between Pusztai and MPs and even congratulated him afterwards, but the meeting never happened. ‘You cannot argue about scientific facts without saying something scientific. They were downright unfair to me,’ says Pusztai. ‘But they had to destroy me so that Jack Cunningham, the Enforcer could say there was no credible evidence’ against GM.[36]

The committee ignored Pusztai’s submitted evidence. This concluded ‘the existing data support our original suggestion that the consumption by rats of transgenic potatoes expressing GNA has significant effects on organ development, body metabolism and immune function that is fully in line with the significant compositional differences between transgenic and corresponding parent lines of potatoes’. This, contrary to the committee’s report, does not contradict what Pusztai said on World in Action.[37]

Part of that submitted evidence is the ‘preliminary’ independent statistical analysis of Pusztai’s work that was published by the Scottish Agriculture Statistical Service and called ‘high and reliable quality’ by one Royal Society reviewer. The summary states that ‘differences in organ weights between rats on different diets, including those between genetically modified and parent potatoes and those between transgenically expressed GNA and added GNA, were larger and more frequent than could be attributed to chance.’[38] This sentence was omitted by the committee in its final report.

Buried deep in the statistical analysis was data that showed that there was not only a problem with the GM potatoes, but also that damage was caused by the construct or Cauliflower Mosaic Virus promoter, which caused ‘significant’ damage to the pancreas, liver, small intestine and brain. ‘Both in the transgene and in the construct, there was statistically significant effect – this is not my analysis, this is from the independent analysis’ says Pusztai.

The committee did quote the sentence from the statistical analysis that said ‘no consistent pattern of changes in organ weights’, had been determined, as if this undermined Pusztai’s work. However Pusztai argues that the committee either did not understand or chose to ignore the fact that the four different experiments were designed to look at four different things and therefore no consistent changes in organ weights should have been expected.

The statistical analysis had concerns about the designs of the experiments, a point picked up on by the committee. But then, argues Pusztai, they made a huge mistake. ‘Dr Pusztai told us that in his 110 day feeding trials, “no differences between parent and GM potatoes could be found”. This contradicts his statement on World in Action’, they said. Actually it does no such thing, he retorts. The experiments had been designed for the rats to grow at the same rate, but in order for this to happen the rats fed GM potatoes were given extra protein. This extra protein is the measure of the growth difference.

As Pusztai explains: ‘The nutritional basis of comparison is that you cannot compare anything that contains different amounts of protein or different amounts of energy or different amounts of vitamins or salt. This is the cornerstone of nutrition. The extra amount of protein that you have to add or compensate for is the measure of the difference in nutritional value. The measure of the compensation is the measure of the growth retardation’.

The Select Committee also had a confidential draft of The Lancet paper that had been submitted to the journal earlier in the year. Although this was later published by the UK’s top medical journal with ‘no significant changes’, the Select Committee ignored that, too. If the Select Committee wanted to discredit Pusztai, they achieved their aim. ‘The scientist who was at the centre of the controversy of genetically modified food has been condemned in two highly influential reports published today,’ said one news report. ‘Research suggesting that GM foods could be a health hazard has been thoroughly discredited’, ran ITN.[39]

It is beyond coincidence that The Royal Society and the Science and Select Committee published on the same day and that the ACNFP and the Committee on Toxicity of Chemicals in Food, Consumer Products and the Environment also published that week. The reason for the coordinated counter attack was simple. The Government was desperate to ‘try and draw a line’ under the GM affair.

Back in December 1998, the government had initiated a review of the regulatory system as it stood on GM.[40] This review had been partly scuppered by the Pusztai fall-out. Now the government had to regain the initiative. Political insiders say that pressure was put on the Science and Technology Committee and The Royal Society to discredit Pusztai, thereby enabling the government to take control again.

This behind-the-scene coordination was partly revealed by a memo showing that the government had set up a ‘Biotechnology Presentation Group’, which included senior Ministers. A meeting was held on 10 May when Jack Cunningham, the Cabinet Enforcer, Tessa Jowell from the Department of Health, Jeff Rooker, the Food Minister and Michael Meacher, the Environment Minister were present, and the memo is illuminating. A decision was taken to ‘present the government’s stance as a single package by way of an oral statement in the House. This would allow the government to get on the front foot’.

Part of the government ‘package’ was the paper by the CMO/CSA on GM foods that had been proposed at the secret cross-departmental meeting in February. The leaked memo revealed how ‘it would not be possible to publish this paper until after The Royal Society report on the Pusztai experiment’ and therefore the Office of Science and Technology ‘should attempt to establish The Royal Society’s intentions on timing’.[41] This is exactly what happened. On 21 May, just three days after The Royal Society and Select Committee published – Jack Cunningham stood up in the House of Commons: ‘Biotechnology is an important and exciting area of scientific advance that offers enormous opportunities for improving our quality of life,’ said Cunningham. ‘In agriculture, genetic modification has the potential to ensure the more efficient production of food that is more nutritious, tastes better and requires fewer pesticides. That is just the start. There are many real and exciting benefits and potential benefits, but the technology is new and the risks must be rigorously assessed.’

As had been planned, Cunningham announced the publication of a report by the CMO, Professor Liam Donaldson, and the CSA, Sir Bob May, on genetically modified food. This concluded that: ‘There is no current evidence to suggest that the genetically modified technologies used to produce food are inherently harmful’.[42]

The Chief Scientific Adviser at the time, Sir Bob May, believed that ‘GM is ‘a vital industry of the future.’[43] May was on The Royal Society Council at the time of the Pusztai review, although The Royal Society is adamant that May ‘was not involved in the review and absented himself from Council when the item was discussed’.[44] Sir Bob May later left the government to become President of The Royal Society. May is another of the influential scientists from the Zoology Department at the University of Oxford, closely linked to Sir John Krebs at the FSA and Professor Roy Anderson, whose controversial models were used in the foot and mouth crisis. Anderson and May have co-authored two books.[45] Backed by May’s and Donaldson’s report, as well as The Royal Society, Cunningham laid his killer punch: ‘The Royal Society this week convincingly dismissed as wholly misleading the results of some recent research into potatoes, and the misinterpretation of it’, said Cunningham. ‘There is no evidence to suggest that any GM foods on sale in this country are harmful. The government welcomes open, rational and well-informed debate. That is the best way to safeguard the public interest. We regret that some political, some media and other treatment of the issues has not served the public well’.

In a further move to reassure consumers, Cunningham announced the setting up of ‘two new advisory bodies. The Human Genetics Commission will advise us on applications of biotechnology in health care and the impact of human genetics on our lives. The Agriculture and Environment Biotechnology Commission will cover the use of biotechnology in agriculture and its environmental effects’. He also announced the formation of a surveillance unit.[46]

If Cunningham hoped that Pusztai was buried, he was wrong. At the end of May, the medical journal, The Lancet, entered the fray, criticizing Pusztai’s ‘unwise’ decision to appear on World in Action. But the journal said the research was necessary. In view of the ‘unbridled commercial approach to genetic modification, it is perhaps not surprising that companies have paid little evident attention to the potential hazards to health of genetically modified foods’, wrote the journal in an Editorial. Most spectacularly, The Lancet attacked The Royal Society’s attack on Pusztai, as a ‘a gesture of breathtaking impertinence to the Rowett Institute scientists who should be judged only on the full and final publication of their work’. In conclusion, The Lancet noted that the ‘issue of genetically modified foods has been badly mishandled by everyone involved’.[47]

Also at the end of May 1999 the Pusztais left Aberdeen for five days. On their return they were met at the airport. ‘There’s been a break-in’ they were told. An initial search of the house established that 30 bottles of Pusztai’s malt whisky collection and some foreign currency were missing. On their second search the Pusztais realized that the bags that contained all their data from the Rowett had been stolen. This break-in was followed by a further break-in at the Rowett at the end of the year. It was only Pusztai’s old lab that was broken into, the burglar managing to get past the tight security.

The Royal Society Working Group

So who was ultimately responsible for the ‘impertinent’ report that condemned Pusztai so hastily and readily? In May 1999, Michael Gillard, Laurie Flynn, and I began to investigate The Royal Society, working for The Guardian. The Royal Society did not like being under investigation itself. The Society wrote to Alan Rusbridger, The Guardian’s editor complaining that Michael Gillard’s ‘threatening tone and inaccurate analysis’ was ‘unacceptable’ and ‘inappropriate in a paper of The Guardian’s standing.’[48]

According to The Royal Society, ‘Responsibility for our conclusions lies with the working group and with the Council of the Society… Following standard practice, the names of these referees will remain confidential. I can, however, assure you that we went to great lengths to choose people with relevant expertise and with no vested interests that could be held to affect their scientific judgement in this matter’.[49]

The Royal Society also clarified that ‘We selected the team of reviewers by identifying the expertises needed (nutrition, statistical analysis, immunology etc, as listed in our published report) finding the strongest individuals with those expertises, setting aside any who had previous involvements that might be regarded as potentially distorting their judgement, and setting aside also any who had commented publicly on the Pusztai affair.’ They noted that members of the Working Group were selected by the same process.[50]

The Royal Society is run by a Council of 21 Fellows, who are led by five officers, the President, who was at that time Sir Aaron Klug; the Treasurer, Sir Eric Ash; the Biological Secretary, Patrick Bateson; the Physical Secretary, then Professor John Rowlinson; and the Foreign Secretary, then Professor Brian Heap. The council, led by these five officers, along with Pusztai’s working group, were responsible for the findings. They were of course guided by the reviewers, who remained anonymous.

Despite these assurances that people involved in the decision making had not commented on the Pusztai affair, they had. Three Council officers, Professor Bateson, Professor Heap and Sir Eric Ash and one person from the working group, Professor William Hill, had already implicitly criticized Pusztai in a letter signed by 19 fellows on 22 February.[51]

Four key people involved, including the Chair of the working group, Noreen Murray, as well as Professor Heap, Rebecca Bowden and Sir Aaron Klug were all part of an earlier working group issued by The Royal Society in September 1998. Their report, entitled ‘Genetically Modified Plants for Food Use’ was broadly seen as being positive, with a few reservations. The chairman of the working group was Professor Lachmann, the then Biological Secretary of the Society and a known GM enthusiast,[52] who was later accused of threatening the Editor of The Lancet about publishing Pusztai’s work.

The Foreign Secretary, Brian Heap, was on The Royal Society Working Group and the Nuffield Council on Bioethics Working Group at the same time. In May 1999, the Nuffield Council’s report on GM crops concluded that: ‘GM crops represent an important new technology which ought to have the potential to do much good in the world provided that proper safeguards are maintained or introduced’.[53]

Of the six members of the working group, although they may not have been involved personally with biotech companies, four were or had been employed in an Institute with biotech connections. One, Professor William Hill, was also the Deputy Chair of the Roslin Institute, famous for genetically modifying animals and for cloning Dolly the sheep who died prematurely in 2003.[54]

The Lancet

When the World in Action programme aired in 1998, some samples of the rat gut still lay unexamined in Stanley Ewen’s laboratory at the University of Aberdeen. ‘Once the programme had gone out in August, I knew that I would have to do some extra work’, says Ewen, in his first in-depth interview since semi-retiring. When Pusztai had spoken about what they had seen in the lab, Ewen still had to undertake the detailed histology, because other work commitments had kept him from analysing the samples.

Ewen and Pusztai intended to go to the scientific meeting in Lund in November 1998. So, in September and October, Ewen worked on the rats and started to get results. He says he was meticulous with the experiments that were done ‘blind’ so not as to prejudice the outcome. He then collated and photographed the results ready to present in November. ‘I realised that there was a very real difference’, he says. ‘I presented the results. I then refined the measurements and refined the technology yet more’.

‘I thought about it for so long and made so many measurements on at least three to four occasions just to make sure I was not introducing any bias’, continues the pathologist. ‘Eventually when our paper was published, I was startled to find that that was the very accusation that was being made. There was no way I could bias them. I was simply reading all the measurements into a computer just using reference numbers, and once all the data was collected, then they were analysed statistically. Ultimately I repeated it five times to make sure that any bias was washed out of the system.’

‘To me it was absolutely certain that there was a real difference,’ Ewen maintains. ‘Although it didn’t necessarily happen to the same extent to every animal in the group, but you would never expect that in biology. Three or four would show a very marked growth effect and the other two wouldn’t be quite so marked. Objective measurements in histology are a relatively recent thing, in the old days it was quite accepted that if you saw a difference, your judgement was never questioned. You don’t measure cancer cells, you just know by your own experience that the tumour is malignant and everyone accepts it.’

‘With this particular technique, it is a very exacting test. Not only did I show that the there was true elongation of the crypt, but that the number of cells increased… even the number of cells in subsequent work which has not been published – all these parameters increased in the GM group.’

Pusztai and Ewen submitted their paper to The Lancet. Ewen faxed a copy of the article to the Rowett before publication, as Pusztai was still required to show them any papers based on his work there. However publication was delayed by two weeks for technical reasons. ‘The rubbishing brigade had been given two weeks to do the dirty on the article. I was almost sure they would stop it,’ says Pusztai.

First of all came the misinformation. ‘Scientists Revolt at Publication of “Flawed” GM Study’, ran The Independent, ‘the study that sparked the furore over genetically modified food has failed the ultimate test of scientific credibility’. Written by science editor, Steve Connor, it continued that ‘research purporting to show that rats suffer ill-health when fed GM-potatoes has been judged as seriously flawed and unworthy of being published by a peer-reviewed scientific journal’. Connor said that the referees were against publication.

One reviewer, Professor Pickett from the Institute of Arable Crop Research (IARC) at Rothamstead in Hertfordshire, a plant scientist, was so enraged that he decided to go public, breaking the scientific rule that reviewers should remain anonymous. ‘It is a very sad day when a very distinguished journal of this kind sees fit to go against senior reviewers,’ said Pickett.[55]

The misinformation spread to other newspapers. The Daily Telegraph reported that ‘rejecting advice from its reviewers, The Lancet is to publish the now notorious GM potato research on Friday’.[56] Even the Chief Executive of the BBSRC, the research council with responsibility for genetic engineering who is a Fellow of The Royal Society, Professor Ray Baker, said ‘It is irresponsible for The Lancet to publish a paper which has been deemed unworthy of publication by referees’.[57]

But both The Independent and BBSRC were wrong. According to Dr Richard Horton, the editor of The Lancet: ‘What Doctor Pickett didn’t know and what Steve Connor from The Independent didn’t know was that we had sent the work to six reviewers and that the clear majority were in favour of publication. Of the five technical experts four were in favour of publication, but one was firmly against, one was in favour of publication, but felt it was flawed, the others were in favour for its scientific merit’.

So of the six reviewers four were in favour of publication on scientific merit. ‘A clear majority of The Lancet’s reviewers were in favour,’ says Horton. ‘Having reviewers disagree whether research should be published is absolutely normal, that’s what surprised me about The Independent piece. That’s how science progresses.’

Then Horton asks questions that should have been answered by now. ‘The Pusztai data raise several new hypotheses, for example, are the changes that he has observed really harmful or are they benign? Are the changes that he has observed found in humans who have taken this particular lectin?’ These questions, The Lancet Editor says, ‘are lines of investigation that must be urgently pursued. Of itself his research does not prove one way or the other that GM foods are either harmful or safe. It does open up important avenues of investigation. All scientists should welcome that’. Then came the ‘threats’. Three days after The Independent article, Richard Horton received a phone call from Professor Lachmann, the former Vice-President and Biological Secretary of The Royal Society and President of the Academy of Medical Sciences. Lachmann had chaired the 1998 Royal Society Working Group report on GM Food and was a known GM supporter. He was also a consultant to Geron Biomed, which marketed the cloning technology behind Dolly the sheep, and a nonexecutive director of the biotech company Aprodech. In addition, Lachmann was on the scientific advisory board of the pharmaceutical giant SmithKlineBeecham.[58]

In July, Lachmann had attacked The Lancet and the British Medical Journal for ‘aligning’ themselves ‘with the tabloid press in opposition to The Royal Society and Nuffield Council on BioEthics’. It was also, wrote Lachmann, ‘disturbing and unusual for an editorial in The Lancet to be factually so inaccurate’.[59]

Lachmann made a bold statement saying that: ‘There is no experimental evidence nor any plausible mechanism by which the process of genetic modification can make plants hazardous to human beings.’ He also added that Pusztai’s potatoes were ‘never intended to be grown as a food crop’. What the campaign of ‘vilification’ against GMOs ‘ does to the science base and the prosperity of the UK may be serious’, wrote Lachmann.[60]

According to Horton, Professor Lachmann threatened that his job would be at risk if he published Pusztai’s paper, and called Horton ‘immoral’ for publishing something he knew to be ‘untrue’. Towards the end of the conversation Horton maintains that Lachmann said that if he published this would ‘have implications for his personal position’ as editor. Lachmann confirms that he rang Horton but vehemently denies that he threatened him.[61]

The Guardian broke the story of Horton being threatened on 1 November 1999.[62] It was the front-page lead. It quoted Horton saying that The Royal Society had acted like a Star Chamber over the Pusztai affair. ‘The Royal Society has absolutely no remit to conduct that sort of inquiry.’[63]

Edited from the final published version in The Guardian was a lot of detail, including a paragraph outlining The Royal Society’s financial support ‘from oil, gas and nuclear industries and three large biotech companies’.[64] Gone also was a quote from Rebecca Bowden, who had coordinated the peer-review process of Pusztai’s work. Bowden had worked for the Government’s Biotechnology Unit at the Department of the Environment, before joining The Royal Society in 1998. She talked about what The Guardian labelled a ‘rebuttal unit’. ‘We have an organization that filters the news out there’, said Bowden. ‘It’s really an information exchange to keep an eye on what’s happening and to know what the government is having problems about … its just so that I know who to put up – more of a forewarning mechanism … If we’ve already got a point of view then we push it.’[65]

In response The Royal Society argued that it ‘was in no way involved in trying to prevent publication of the Pusztai paper’ and denied the existence of a rebuttal unit. It maintains that it never tried to block The Lancet publication. But Horton said he had also received an email correspondence from John Gatehouse at Durham who was involved in the design of Pusztai’s potatoes, which, although it was sent to him, was copied by email to Rebecca Bowden at The Royal Society. Horton was surprised at this, why was Bowden being sent copies of emails that had nothing to do with her, he thought, was she coordinating the anti-Pusztai response?[66]

On 16 October The Lancet printed the paper by Pusztai and Ewen. The conclusion of the Ewen/Pusztai research was that ‘Diets containing genetically modified (GM) potatoes expressing the lectin Galanthus nivalis agglutinin (GNA) had variable effects on different parts of the rat gastrointestinal tract. Some effects, such as the proliferation of the gastric mucosa, were mainly due to the expression of the GNA transgene.

However other parts of the construct or the genetic transformation (or both) could also have contributed to the overall biological effects of the GNA-GM potatoes, particularly on the small intestine and caecum.’[67]

Horton pointed out that ‘publication of Ewen and Pusztai’s findings is not, as some newspapers have reported a “vindication” of Pusztai’s earlier claims’.[68] The journal also ran a ‘safeguard’ commentary that criticized Ewen and Pusztai’s data for being incomplete. The results were ‘difficult to interpret and do not allow the conclusion that the genetic modification of potatoes accounts for adverse effects in animals’.[69] The Lancet also published another research letter by scientists at the Scottish Crop Research Institute and the University of Dundee, led by Brian Fenton. These scientists had also examined the snowdrop lectin, GNA. They concluded that there was evidence of snowdrop lectin binding to human white cells ‘which supports the need for greater understanding of the possible health consequences of incorporating plant lectins in to the food chain’.[70] Both the Fenton and Pusztai data ‘raise issues about the design of studies on safety’, concluded one of The Lancet commentators.[71]

Horton and The Lancet were once again attacked for publishing the work by the biotechnology industry and The Royal Society after it appeared. Peter Lachmann called the paper ‘unacceptable’. The Biotechnology Industry Association criticized The Lancet’s decision to publish as breaking ‘unfortunate new ground for a scientific journal. Put simply, The Lancet has placed politics and tabloid sensationalism above its responsibility to report and assess new science’. Sir Aaron Klug, the President of The Royal Society, also joined in the criticism.[72]

In response to this criticism, especially that emanating from The Royal Society and Lachmann, Ewen and Pusztai responded by writing that: ‘These methods were approved by independent statisticians. Lachmann says that the experiments need to be repeated. We would be happy to oblige. If our experiments are so poor why have they not been repeated in the past 16 months? It was not we who stopped the work on testing GM potatoes expressing GNA or other lectins or even potatoes transformed with the empty vector, which are now available. If Lachmann represents the view of the Academy of Medical Sciences on GM-food safety he should use his influence to make funds available for the continuation of this work in the UK’.[73]

But the final word was left to The Lancet’s editor, Dr Richard Horton, who wrote, ‘Stanley Ewen and Arpad Pusztai’s research letter was published on grounds of scientific merit, as well as public interest’. What Sir Aaron Klug from The Royal Society cannot ‘defend is the reckless decision of The Royal Society to abandon the principles of due process in passing judgement on their work. To review and then publish criticism of these researchers’ findings without publishing either their original data or their response was, at best, unfair and ill-judged’.[74]

But the threats continued: ‘After the letters were published, I got feedback “by proxy”,’ says Ewen. ‘I got a warning that I had to cut down my profile. I was never actually warned by the higher echelons of the university, but it trickled down to me, via my PhD student.’ The university did not like the fact that Ewen had criticized Peter Lachmann, the President of the National Academy of Medical Sciences, and a Royal Society member. ‘Because we attacked him, it was bad for any university. I was told not to be so provocative.’

The publication of The Lancet paper was going to have a detrimental effect on Ewen’s long-term employment with the University of Aberdeen, and rather than get recognition for his work, all he seemed to get was anguish. Ewen learned that ‘several groups of people had recommended I be considered’ for an academic award. ‘I was told that the university had no interest.’

‘I felt that I had done so much work that had been unacknowledged’, says the pathologist. ‘I felt that I deserved some recognition, but this was being blocked at a very high level by other spokespersons. It wasn’t helpful to my career. When you do these sorts of things it is very difficult for your pension. Because that is what it comes down to in the final analysis: money’. Eventually he felt that he had no option left and Ewen retired on the 26 March, 2001. He now works as a consultant to the NHS.

‘I wanted to draw two lines under what I considered to be a hostile situation. Whereas instead of saying well done for getting a paper into The Lancet, for being at the cutting edge of this debate, I thought that I was being pilloried. It came to the point that I thought they would have regarded me more highly if I had never done this work.’

Ewen was also subjected to playground politics by the UK scientific establishment. He recalls a WHO meeting in early 2000 that he attended to discuss GM foods. ‘It was an empty room and I put my briefcase down on the table, but I didn’t know who I was sitting next to, and it turned out that it was a member of the ACNFP. When he realised he was sitting next to me, he moved’.

The Royal Society revisited

In February 2002, the latest Royal Society report on GM crops was published, marking a much more cautious line being taken by the Fellows. ‘British Scientists Turn on GM Foods’, ran The Guardian.[75] It was effectively a U-turn from their previous positions.

Jim Smith, who had sat on the Pusztai Working Group, chaired the latest Working Group. Whilst known GM proponents sat on the committee, there were also known GM sceptics. The scientists warned that, although in their opinion, there were no known health effects from existing GM foods on the market, ‘it is possible’ they argued ‘that GM technology could lead to the unpredicted harmful changes in the nutritional status of foods’.[76]

The scientists argued that it was the ‘vulnerable’ populations who might suffer most: babies, people prone to allergies, pregnant and breastfeeding women, people with chronic diseases and the elderly. They recommended that improved safety testing within the European Union was needed before more GM crops were approved. There also needed to be a tightening of regulations, especially with respect to potential allergies and also GM baby foods.

Deep in the report was a paragraph on Pusztai. It read: ‘In June 1999, The Royal Society published a report, review of data on possible toxicity of GM potatoes, in response to claims made by Dr Pusztai (Ewen and Pusztai, 1999). The report found that Dr Pusztai had produced no convincing evidence of adverse effects from GM potatoes on the growth of rats or their immune function.’ The Fellows continued: ‘It concluded that the only way to clarify Dr Pusztai’s claims would be to refine his experimental design and carry out further studies to test clearly defined hypotheses focused on the specific effects reported by him. Such studies, on the results of feeding GM sweet peppers and GM tomatoes to rats, and GM soya to mice and rats, have now been completed and no adverse effects have been found (Gasson and Burke, 2001).’[77]

In the first sentence, The Royal Society referenced the article published by Pusztai and Ewen in The Lancet to the ‘claims they had examined’. This is not true as The Royal Society’s report was published months before The Lancet article and when The Royal Society had only reviewed part of Pusztai’s data. Moreover, The Royal Society went on to argue that feeding studies with GM sweet peppers, GM tomatoes and GM soya ‘have now been completed’ and ‘no adverse effects have been found’. They referenced this to a paper by Gasson and Burke. This is not a primary research paper but an ‘opinion’ piece written by two pro-GM scientists, Michael Gasson and Derek Burke, and published in Nature Reviews Genetics.[78]

Gasson and Burke outline their argument as to why it is safe to eat GM foods: ‘US citizens eat GM soya without any detectable effect on their health... Many consumers eat GM foods. No significant adverse effects have yet been detected on human health’. The absence of evidence rather than the evidence of absence is being used to argue that something is safe. What do they mean by ‘detectable’ or ‘significant’ and notice the ‘yet been detected’, implying that there might be health effects in the future?

But the situation becomes even more hypocritical if one looks at the supporting evidence. The Royal Society report cites two studies to dismiss Pusztai’s claims, and these are referenced to the Gasson and Burke paper. One group fed ‘transgenic sweet peppers and tomatoes to rats’, the other fed ‘GM soya to mice and rats, with no adverse effects’.[79]

The reference for the sweet pepper and tomatoes study is ‘Chen, ZL et al, Safety assessment for transgenic sweet pepper and tomato (submitted)’. The last word – submitted – is important. It means a paper has been submitted to a journal for publication. The crucial fact is that it has not yet been published, it is not peer-reviewed and it may never be published, if the peer reviewers advise against publication. So The Royal Society were attacking Pusztai on [the basis of] unpublished and un-peer-reviewed work, two years after they condemned him for speaking to the media without publishing peer-reviewed work.

The hypocrisy of The Royal Society angers Pusztai. ‘They had to say something and they thought they would get away with it.’ Pusztai argues that the other reference quoted by The Royal Society was invalidated because the rats were basically starving. In a peer-reviewed article published in Nutrition and Health Pusztai outlined his critique of the paper. ‘Although the design of this long-term study was acceptable its execution was poor’, wrote Pusztai. ‘Thus, the growth of rats was unacceptably low and only amounted to just over 20g over 105 days and the growth of mice was zero.’ ‘In fact,’ concluded Pusztai, ‘this study gave a good example of how under starvation conditions most physiological/ metabolic/immunological parameters could become unreliable.’[80]

But The Royal Society dismisses Pusztai’s concerns and has shifted its opinion on what is now deemed acceptable science. ‘The Royal Society recognizes how important it is that research scientists should expose new research results to others able to offer informed criticism before releasing them into the public arena. The unpublished work of Professor Chen has been discussed at international conferences (for example the 6th International Symposium on Biosafety of GMOs, July 2000, Saskatoon, Canada) and we look forward to this work being published.’[81]

When asked about this discrepancy, The Royal Society confirms that although the Chen work remained unpublished, ‘it had been discussed at international scientific conferences’. Ironically by their own definition, the Pusztai and Ewen research is validated. The Society also calls Gasson and Burke’s work ‘primary research,’ although it is a literature review – no lab work was undertaken. ‘An opinion article under normal circumstances could not be taken as primary research,’ argues Dr Tom Wakeford, a Royal Society funded researcher from the University of Newcastle.

The highly selective use of references also angers Dr Stanley Ewen, who wrote to The Royal Society. He pointed out to The Royal Society that a paper published in Natural Toxins in the autumn of 1998 showed potential evidence of harm from eating GM food.[82] The paper concluded that ‘mild changes are reported in the structural configuration of the ileum of mice fed on transgenic potatoes’ and ‘thorough tests of these new types of genetically engineered crops must be made to avoid the risk before marketing’.[83]

‘Hence I remain concerned’, says Ewen, ‘that ingestion of raw GM foodstuff by humans could accelerate the polyp cancer sequence in the colon as the uncooked plant cells wall will only be broken down by colonic bacteria’.

But the fundamental flaw in the scientific establishment’s response is not that they try and damn Pusztai with unpublished data, nor is it that they have overlooked published studies, but that in 1999, everyone agreed that more work was needed. Three years later, that work remains to be undertaken. Pusztai maintains that you ‘cannot by any stretch of the imagination, call it [the Chen paper] a repeat of our experiments.’ A scientific body, like The Royal Society, that allocates millions in research funds every year, could have funded a repeat of Pusztai’s experiments. Is it that it is easier to say there is no evidence to support his claim, because no evidence exists, than it is to say that no one has looked?

By trying to sound more cautious on GM, the Society tied itself in a mess. On the one hand, the scientists argued that there was no evidence of any harm caused by GM crops, but on the other The Royal Society Fellows took issue with the very safety mechanism – substantial equivalence – designed to make sure products were safe. But it had to act. Since the late 1990s public concern about the health and environmental effects of GM crops in the UK had become more intransigent, a fact reflected by the Fellows, who recognized ‘public concern’ about GM technology.

But it was their international peers that had forced the shift in thinking. A year earlier, in February 2001, the Royal Society of Canada had published a report into GM, that had castigated the notion of substantial equivalence. Their Expert Panel recommended that ‘the primary burden of proof be upon those who would deploy food biotechnology products to carry out the full range of tests necessary to demonstrate reliably that they do not pose unacceptable risks.’84 ‘When it comes to human and environmental safety’, the Chairman, Conrad Brunk of the University of Waterloo, said ‘there should be clear evidence of the absence of risks; the mere absence of evidence is not enough’.[85]

As we shall see in the next chapter, our regulatory environment is one where absence of evidence seems to have taken precedence over evidence of absence. The Royal Society believe that ‘there is no reason to doubt the safety of foods from GM ingredients that are currently available, nor to believe that genetic modification makes food inherently less safe than their conventional counterparts’. But how true is this?

Notes

1 Cabinet Office (1999) GM Foods and Crops: Policy and Presentation Issues, Restricted, 19 February.

2 Royal Society, (1999) Royal Society Experts to Probe GM Food Concerns, Press Release, London, 19 February

3 Klug, Sir A (1999) Speech Given to the Annual Luncheon of the Parliamentary and Scientific Committee, London, 23 February.

4 Royal Society (1999) Letter From a Group of Fellows at The Royal Society, London, 22 February.

5 Meek, J (20001) ‘Scientific Elite Put Under Microscope’, The Guardian, London, 17 March, p15.

6 House of Commons Science and Technology Committee (2002) Government Funding Of the Scientific Learned Societies, Fifth Report of Session 2001-02, Volume 1: Report and Proceedings of the Committee, 1 August, p44.

7 Leake, J (2002) ‘Royal Society Found Guilty of Keeping out Woman Scientists’, The Sunday Times, London, 28 July, p7.

8 House of Commons Science and Technology Committee (2002) op cit, pp40–43.

9 Wakeford, T (2000) ‘Genetically-Modified Science’, Times Higher Educational Supplement, April.

10 Wakeford, T (2002) Personal Communication with Author, October.

11 Collins, P (2002) Communication with Author, The Royal Society, London, 6 November.

12 See Bøg-Hansen’s website http://plab.ku.dk/tcbh/Pusztaitcbh.htm; Pusztai, A (2002) Interview with Author, November.

13 Ibid.

14 Cox, S (1999) Letter to Arpad Pusztai, London, 15 March.

15 Pusztai, A (1999) Letter to Dr Rebecca Bowden, Aberdeen, 19 March

16 Pusztai, A (1999) Letter to Rebecca Bowden, Aberdeen, 19 March.

17 Ewen, S (1999) Re Royal Society Involvement in the Debate of the Safety of GM Food, Letter to Stephen Cox, Royal Society, 23 March.

18 Cox, S (1999) Letter to Arpad Pusztai, London, 23 March.

19 Anonymous (1999) Hand-written notes, 31 March – the fact that the reviewer had already commented was removed from the typed version Pusztai received in an email from Rebecca Bowden on 10 May 1999.

20 Anonymous (1999) Review of Data on Toxicity and Allergenicity of GM Food, Sent to Pusztai in an email from Rebecca Bowden on 4 May.

21 Anonymous (1999) GM Potatoes, 8 April.

22 Anonymous (1999) Possible Toxicity of GM potatoes, Comments on the Work by Professor Arpad Pusztai, 12 April.

23 Anonymous (1999) comments enclosed in an email sent by Rebecca Bowden to Professor Pusztai, 10 May.

24 Ibid.

25 Pusztai, A (1999) Email to Rebecca Bowden, Aberdeen, 4 May.

26 Bowden, R (1999) Email to Professor Pusztai, London, 10 May; Pusztai, A (2002) Interview with Author, March; Collins (2002), op cit.

27 Bowden, R (1999) Email to Arpad Pusztai, London, 13 May.

28 Pusztai, A (1999) Letter to Stephen Cox, Aberdeen, 12 May.

29 The Royal Society (1999) Review of Data on Possible Toxicity of GM Potatoes, London, 17 May.

30 Collins (2002) op cit.

31 Radford, T (1999) ‘GM Research “Flawed in Design and Analysis”’, The Guardian, London, 19 May, p11; Derbyshire, D (1999) ‘Experts Say Key Research is Flawed’, The Daily Mail, London, 19 May, p6.

32 Pusztai, A et al (1999) ‘Expression of the Insecticidal Bean α-Amylase Inhibitor Transgene Has Minimal Detrimental Effect on the Nutritional Value of Peas Fed to Rats at 30% of the Diet’, Journal of Nutrition, Vol 129, pp1597–1603.

33 Ibid.

34 Science and Technology Committee (1999) Scientific Advisory System: Genetically Modified Foods, The Stationery Office, London, First Report, Volume 1, pxv.

35 Ibid, p30.

36 Pusztai, A (2002) Interview with Author, March.

37 Pusztai, A (2002) The ‘Scientific Advisory System: Genetically Modified Foods’ Inquiry; Memorandum to the Science and Technology Committee, 1999, p2.

38 Horgan. G W and Glasbey, C A (1999) Statistical Analysis of Experiments on Genetically Modified Potatoes at the Rowett Research Institute, Biomathematics and Statistics, Scotland, 1 March.

39 Quotes taken from different news broadcasts on the 18 May 1999.

40 Office of Science and Technology (1999) The Advisory and Regulatory Framework for Biotechnology: Report from the Government’s Review, Cabinet Office, May.

41 Britton, P (1999) Biotechnology Presentation Group, Letter to John Fuller, Private Secretary to the Cabinet Office, 11 May.

42 Cunningham, J (1999) Speaking in the House of Commons; 21 May.

43 Science and Technology Committee (1999) op cit, pxvi.

44 Collins (2000) op cit.

45 Booker, C and North, R (2001) ‘Not the Foot and Mouth Report’, Private Eye, London, p28.

46 Cunningham (1999) op cit.

47 The Lancet (1999) ‘Health Risks of Genetically Modified Foods,’ Editorial, London, Vol 353, No 9167, 29 May, p1811.

48 Cox, S (1999) Letter to Alan Rusbridger, London, 25 May.

49 Collins, P (1999), Letter to Michael Gillard, London, 24 May.

50 Cox, S (1999) Letter to Michael Gillard, London, 17 June.

51 Letter from a Group of Fellows at The Royal Society, 22 February 1999, signed by Brian Heap; Patrick Bateson; Sir Eric Ash; Roy Anderson; Sir Alan Cook; Sir Roger Elliott; Professor William Hill; Louise Johnson; Sir John Kingman; Peter Lachmann, Dr Paul Nurse; Linda Partridge; Dr Max Perutz; Sir Martin Rees; Sir Richard Southwood; Sir John Meurig Thomas; Sir Ghillean Prance; Lord Selbourne; Robert White.

52 Royal Society (1998) Genetically Modified Organisms – the Debate Continues, Press Release, London, September.

53 Nuffield Council on Bioethics (1999) Genetically Modified Crops: the Ethical and Social Issues, Nuffield Council, London, p136.

54 The Working Group was chaired by Professor Noreen Murray, Professor of Molecular Genetics at the Institute of Cell and Molecular Biology, University of Edinburgh, whose research is funded by the Medical Research Council. Murray’s Department has links to, amongst others, the Roslin Institute and the Scottish Crop Research Unit. Also from the University of Edinburgh, was Professor William Hill, from the Institute of Cell, Animal and Population Biology at the Division of Biological Sciences. Much of Hill’s work is ‘in collaboration with the Roslin Institute and the animal breeding industry’. According to the Roslin’s annual report, Hill was Deputy Chairman of the Roslin and on its Governing Council. Michael Waterfield was the Head of Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University College London. In 1999 scientists at his department were funded by Unilever, GlaxoWellcome, Glaxo and Glaxo Group Research, amongst others (Cartermill International, Current Research in Britain – Biological Sciences, 13th Edition, pp216–218). Professor Brian Heap had been Director of Research at Roslin and another key biotechnology institute, Babraham. Heap had also held consultancies in the pharmaceutical sector.

55 Connor, S (1999) ‘Scientists Revolt at Publication of “Flawed” GM Study’, The Independent, London, 11 October, p5.

56 Highfield, R and Aisling, I (1999) ‘Study is Published and Damned’, The Daily Telegraph, London, 13 October, p 21.

57 BBSRC (1999) BBSRC Concern About GM Paper in The Lancet, BBSRC Press Release, Swindon, 13 October.

58 Flynn, L and Gillard, M S (1999) ‘Pro-GM Food Scientist “Threatened Editor”’, The Guardian, London, 1 November.

59 Lachmann, P (1999) ‘Health Risks of Genetically Modified Foods’, The Lancet, London, Vol 354, 3 July, p69.

60 Ibid.

61 Flynn and Gillard (1999) op cit.

62 Ibid.

63 Ibid.

64 Gillard, M S, Rowell, A, Flynn, M (1999), Draft of Copy, Legalled and Changed, 11.30 am, 26 October.

65 Ibid.

66 Horton, R (1999) Interview with Author and Michael Gillard, October.

67 Ewen, S W B and Pusztai, A (1999) ‘Effects of Diets Containing Genetically Modified Potatoes Expressing Galanthus Nivalis Lectin on Rat Small Intestine’, The Lancet, London, Vol 354, 16 October, pp1353–1354.

68 Horton, R (1999) ‘Genetically Modified Foods: “Absurd” Concern or Welcome Dialogue,’ The Lancet, London, Vol 354, 16 October, pp1314–1315.

69 Kuiper, H A et al (1999) ‘Adequacy of Methods for Testing the Safety of Genetically Modified Foods’, The Lancet, London, Vol 354, 16 October, pp1315–1316.

70 Fenton, B et al (1999) ‘Differential Binding of the Insecticidal Lectin GNA to Human Blood Cells,’ The Lancet, London, Vol 354, 16 October, pp1354–1355.

71 Kuiper et al (1999) op cit.

72 The Lancet (1999) ‘GM Food Debate’, London, Vol 354, 13 November, pp1725–1729.

73 Ewen, S and Pusztai, A (1999) Authors’ Reply, The Lancet, London, Vol 354, 13 November, pp1726–1727.

74 Horton, R (1999) ‘GM Food Debate’, The Lancet, London, Vol 354, 13 November, p1729.

75 Brown, P (2002) ‘British Scientists Turn on GM Food’, The Guardian, London, 5 February, p7.

76 The Royal Society (2000) Genetically Modified Plants for Food Use and Human Health – An Update, London, February, p3.

77 Ibid; The Royal Society, Safety Checks for GM Foods Must be Better, Says Royal Society, Press Release, London, 4 February.

78 Gasson, M and Burke, D (2001). ‘Scientific Perspectives on Regulating the Safety of Genetically Modified Foods’, Nature Reviews Genetics 2, March, pp217–222.

79 Ibid.

80 Pusztai, A (2002) ‘Can Science Give us the Tools for Recognising Possible Health Risks of GM Food’? Nutrition and Health, Vol 16, pp73–84.

81 Smith, J (2002) Letter to Dr Pusztai, London, 26 March.

82 Ewen, S (2002) Re: The Royal Society GM Plants Report, Email to Josephine Craig, 14 February.

83 Fares, N and El-Sayed, A (1998) ‘Fine Structural Changes in the Ileum of Mice Fed on δ Endotoxin-Treated Potatoes and Transgenic Potatoes’, Natural Toxins, Vol 6, pp219–233.

84 The Royal Society of Canada (2001) Expert Panel on the Future of Food Biotechnology, Ottawa, px; The Royal Society of Canada (2001) Expert Panel Raises Serious Questions About the Regulation of GM Food, Press Release, Ottawa, 5 February.

85 Ibid.

Copyright Andy Rowell, 2003